Nurses place incredibly high expectations on themselves, mainly because we know if we make a mistake or overlook something, the consequences can be catastrophic. That said, we’re also human, and like all humans, we’re fallible, whether we like it or not.

In my last post, I described how a heavy cognitive load—which is when the working memory is overwhelmed—can contribute not only to errors, but also to stress and burnout. In this article, I’ll describe common situations and risk factors nurses face that raise their cognitive load, and how they can affect patient safety and outcomes. The post also will explain what hospitals and health systems can do to lighten the cognitive load while at the same time enabling continuous vital signs monitoring of their patients.

RELATED READING: A Nurse’s Greatest Fear: Missing Signs of Preventable Patient Deterioration (Part 1)

Risk Rises Outside of ICU

Patients in intensive care or other critical care units are certainly higher risk due to the severity of their illnesses or injuries. In these areas, however, they are monitored more closely by clinicians than in other units since the nurse-to-patient ratio is typically 1:2, or even 1:1 for the sickest patients. As an RN in a surgical/trauma ICU, I was able to focus much more attention as a result of fewer patients in my care, increasing the likelihood of recognizing a subtle change early on and intervening appropriately.

On the other hand, in the non-critical medical-surgical areas of the hospital, things can be very different. Not only is the nurse-to-patient ratio 1:5, or even 1:7, but patients aren’t ordinarily monitored continuously like in the ICU. Instead, vital signs are measured every four, six, or maybe eight hours. Additionally, in order to keep noise levels down, doors are kept closed, and the large glass windows that allowed me to keep an eye on my patients in the ICU even when I wasn’t in the room, are replaced with solid walls, further diminishing my ability to keep watch over my patients. Even when continuous pulse ox or capnography is employed, it’s difficult, under these conditions, to hear alarms coming from the devices. There just isn’t the same level of visibility into what is happening.

Add to that all of the other responsibilities—as a nurse, the task list is long and the distractions are many—including answering a call light where the patient is in pain and asking for some relief; checking on critical lab results on another patient; comforting worried family members frustrated because they aren’t getting answers they’re expecting; and getting interrupted by a phone call from a physician. The amount of incoming information can exceed the capacity of our working memories, and something has to give, which can lead to a slip. Then, apply the stresses of being a bedside nurse during a worldwide pandemic caused by a virus we’ve never seen before, and it can all become overwhelming at best. In our normal lives, when we forget to grab a gallon of milk at the grocery store or pay a bill on time, it’s no big deal, but for nurses, one slip can have dire consequences.

Ancillary Risk Factors

Another major challenge for nurses today is the staggering number of patients who enter the hospital with existing chronic diseases, such as heart/cardiovascular disease, chronic lung disease, diabetes, chronic kidney disease, and obesity, not to mention the increasing aged population. According to the CDC’s National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion (NCCDPHP), six in 10 adults in the U.S. have a chronic disease, and 4 in 10 have two or more. In addition to the primary condition that brought the patient into the hospital, these comorbidities create substantially more complex cases for nurses to manage, particularly in patients receiving opioid pain medication that can cause a number of adverse events, such as depression of the respiratory system.

Keep in mind, when it comes to respiration, oxygenation is a distinctly different physiological process from ventilation. Ventilation is the process of taking air into the lungs. Oxygenation is the delivery of oxygen to the tissues where it is put to use, together with glucose, to create energy. Both are essential to maintain life. Pulse oximetry measures the amount of capillary oxygen being carried by the red blood cells but not whether it’s necessarily being used properly to feed the tissues, described by the process of perfusion. It’s also been shown to be a lagging indicator that the patient may be in trouble and receiving inadequate perfusion necessary for cellular function through the delivery of oxygen and the removal of wastes, particularly carbon dioxide. Capnography, on the other hand, measures expired carbon dioxide (EtCO2), the byproduct produced once oxygen has been used by the cells. It has been shown to be “able to identify respiratory depression before clinical examination and before oxygen desaturation,” since EtCO2 levels quickly rise in a patient’s exhaled breath, when he or she isn’t sufficiently breathing in enough fresh, oxygen-rich air, as seen in hypoventilation, airway obstruction, and apnea.

The presence of comorbidities raises the risk of respiratory depression after anesthesia, such as following surgery, or when opioid pain medication is in use. Sadly, it is possible for respiratory depression to go unnoticed until the patient experiences respiratory arrest that can lead to anoxic brain injury, cardiac arrest, or even death. This is of considerable concern whether the opioids are administered by a nurse or by the patient through a PCA pump, especially if the patient is not being continuously monitored or when monitoring SpO2 alone. Of note, one study showed that confirmed cases of Opioid Induced Respiratory Depression (OIRD) occurred in 46% of patients on the general care floor, and a recent database review found that the vast majority of incidents of respiratory depression “occurred within the 24 hours of surgery, and 97% were judged to be preventable.” Those are sobering statistics.

Healthcare systems have begun to recognize that vital signs monitoring periodically, as mentioned earlier, just isn’t enough, so many have employed continuous pulse oximetry in general surgical units. But the Joint Commission states, “Staff should be educated not to rely on pulse oximetry alone because pulse oximetry can suggest adequate oxygen saturation in patients who are actively experiencing respiratory depression, especially when supplemental oxygen is being used – thus the value of using capnography to monitor ventilation.”

Mitigating Risks

So, what can be done to help nurses identify patients whose condition may be decompensating, especially in the hospital’s non-critical care areas, then be promptly notified, so they can intervene quickly in order to have the best probability of turning the situation around?

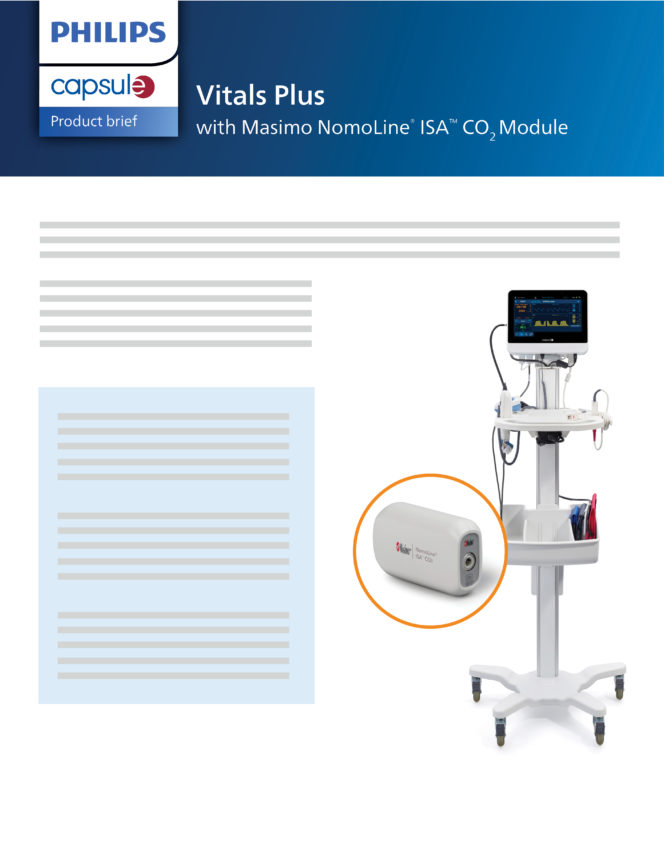

Capsule’s Vitals Plus, with the newly added feature of Masimo’s NomoLine ISA CO2 Module, offers continuous pulse oximetry (CPOX) along with continuous capnography monitoring. An article published in Anesthesia & Analgesia found “the odds of recognizing Post-Operative Respiratory Depression (PORD) was almost six times higher” in patients who were continuously monitored with capnography vs. pulse ox alone and it “allowed for better titration of narcotics and improved pain management” since it provided nurses with tangible clinical data upon which to individualize their care. They concluded that “when continuous capnography monitoring was used in conjunction with CPOX, capnography provided additional information on ventilation that helped herald respiratory depression before oxygen desaturation.”

Additionally, Capsule also offers the Early Warning Scoring System (EWSS) to be deployed on Vitals Plus. Early warning scoring has been shown to identify patients at risk of a serious adverse event (SAE), hours before it occurs, reducing unplanned ICU transfers, length of stay (LOS), and patient mortality—which translate to lower overall cost of care and better patient outcomes. With a configurable algorithm, presentation of trended scores over time, automatic calculation of the patient’s score, and, most importantly, the ability to display each hospital’s unique protocols, including specific next steps at the bedside, the right interventions can be immediately put into action before the clinician ever leaves the room.

And that’s not all. Vitals Plus with EWSS can be deployed with Capsule Surveillance, which provides viewing of all patients’ vital signs and scores at a central station or on the go as well as the ability to send out meaningful, contextual, and actionable notifications to the proper caregiver on a mobile device. This level of vital signs monitoring is incredibly important in the non-critical care areas of the hospital where there is less visibility to serious patient decline. It’s an extra level of supervision that can further decrease the cost of care, and helps fill the gap, giving nurses some peace of mind that they’ll be informed if there’s a significant change in their patients’ conditions, no matter where they might be on the unit.

And Vitals Plus is built on the Capsule Medical Device Information Platform (MDIP) that permits seamless and effortless flow of data to the patient record and any other downstream systems. This not only improves clinical workflow but also reduces cognitive load.

As a nurse working at the bedside, I was fortunate to benefit from such technologies, and I speak from experience when I say it allowed me to focus more keenly on my patients. Now, more than ever, as nurses have added COVID-19 to the many conditions they must manage in their units, our frontline caregivers need support and help to manage the heavy responsibilities they bear.

Learn more about adding capnography to your postoperative workflows with Vitals Plus.

Download